Recently one of Pakistan’s most respected economic mandarins, Mueen Afzal, gave a talk at the Institute of Strategic Studies in Islamabad on the subject of stabilising the Pakistan economy. A recent report says “the country is headed for inevitable default”. Pakistan’s external debt has rocketed to over $124 billion and its domestic debt has exploded to over $140 billion, making a total national debt of over $270 billion — well over a quarter of a trillion dollars.

This comes to over $100,000 for every man, woman and child in Pakistan. This is the odious “debt trap” or rather “death trap” in which 90% of the population of Pakistan is imprisoned for life by the thriving and thieving ruling 10%.

Mueen Afzal said he had been asked three questions. One, could Pakistan manage this debt? Two, was CPEC viable? And, three, are economic experts useful? Mueen sagely responded by saying debt was like an illness and its treatment depended on its severity and on the cooperation of the patient. Similarly, with regards to CPEC he noted it was viable provided the debts incurred were put to good use and repayment obligations and capacity were borne in mind. As for experts, he observed that public finance required practical commonsense more than academic expertise although its importance was undeniable.

Accordingly, stabilising the economy depended on the state of the macro-situation. Pakistan’s imports at over $60 billion per annum were almost twice its exports. The gap was more or less filled by remittances which was on capital account. As long as the trade gap was kept under control the rupee could be kept stable, inflation contained and growth sustained. Otherwise, a vicious circle would set in as foreign exchange reserves would rapidly diminish (sending Pakistan to the ICU of the IMF for the 25th time).

However, to sustain growth over the longer term, the social sectors including child and healthcare, education including vocational education, population growth, infrastructure development, job security, living wages, reduction in corruption, etc would require much greater attention and priority. Unfortunately, there is very little budgetary space for these priorities because of military, administration, and debt repayment expenditures (which are increasingly financed by incurring further debt.) IMF programmes can at best help prepare the ground for longer-term domestic and foreign direct investment which are essential for growth rates that lift all boats. But for this political stability is a prerequisite.

Mueen Afzal mentioned two economists whose writings have fundamentally influenced thinking on development economics. One is Thomas Piketty. According to him, prior to World War I tax revenues of advanced countries like the US, the UK, France and Sweden were never more than 8-10% of GDP since government expenditures were largely for the police, the courts, the judiciary, the military and some infrastructure.

The governance priorities of early industrial capitalism largely served feudal-bourgeoisie interests. It was only after World War I (and the Russian Revolution) that government policies became conscious of poverty. The shared experience of the horrors of modern war from the US civil war and the Franco-Prussian war to the first and second world wars (1870 to 1950) impacted the class basis of politics. As a result, there was a three to four-fold rise in tax revenues to address the needs of veterans and their families who were overwhelmingly from the lower classes that had all suffered the ravages of war.

After World War II and the start of the Cold War, the concept of social welfare as a major principle of governance came to the fore to challenge the appeal of Russian communism. Tax revenues in the advanced industrial countries accordingly dramatically rose to more than 50% of GDP. An awareness of the need to address the consequences of egregious inequalities informed the politics of Western democracies whether ruled by progressive pro-labour or conservative pro-business parties.

Piketty, however, noted the “South Asian conundrum” according to which tax revenues in impoverished underdeveloped and densely populated countries like India and Pakistan remained at 15%–20% of GDP. Despite the socialist or nationalist rhetoric, politicians and bureaucrats presumably regarded poverty as so overwhelming a reality that it could only be managed not resolved (even when drawing up long-term perspective plans).

The other economist mentioned by Mueen was Stefan Dercon who wrote Gambling on Development. He visited Pakistan where he observed there was no need for governmental expertise in public finance which essentially required sensible decision-making. Mueen cited examples of procurement prices for cotton and rice that were above market prices which made no sense as they drained public resources, raised prices for consumers, and could not be sustained.

Similarly, charging below market prices for gas, petroleum and electricity had contributed to the circular debt which had become a monster. He recalled a prime minister telling him that if he did not have the money to provide certain services all he had to do was to ask for it. Apparently, the great man did not realise (or did not care) there were “twin holes” in export and tax revenues as a result of which the people of Pakistan were “paying through their noses” for these services today.

In the same way, Sui gas prices were set with the profitability of the producer in mind instead of the needs of the consumer. As a result, Quetta, which is the capital of Balochistan in which the Sui gas fields are located and is the coldest of all the provincial capitals — and the people of Balochistan are the poorest and most exploited people of Pakistan — was the last to receive Sui gas. Mueen was too polite to draw political conclusions but they were not lost upon his audience.

According to Dercon, “Pakistan’s status quo is untenable and even elites are losing because of it.” Low tax collection, high subsidies, low savings and investments are part of the “elite bargain” in Pakistan. This “regularly leads to macroeconomic and fiscal crises and the need for outside support”. He calls for “a set of incentives for the emergence of a better elite bargain for growth and development”. In other words, an economic zero-sum game between the elites and the people should be converted into a more positive-sum game in which the people can share in the benefits.

This, of course, is a liberal Tory concept of social welfare or ‘third-way’ based economic development. It claims to be realistic in that it minimises business, conservative and reactionary opposition and settles for ‘second best’ solutions on the assumption that ‘the best should not be made an enemy of the good’. Striking a viable balance depends on detailed study of specific social, economic and political situations, and good and responsive governance. As Mueen Afzal rightly says, there are no easy or pat answers. That is why economics is a discipline not a science and economic development is a problem of political economy rather than economics.

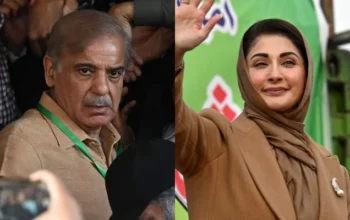

He did not need to mention that the recent elections have brought this reality into national focus like never before as the people of Pakistan now feel their country has become one big Balochistan. Able and sincere politicians will need to learn from the wise counsel of people like Mueen Afzal in order to better serve the people.